“This spring, as never before in modern times, London is switched on,” declared Time magazine in April 1966. “Ancient elegance and new opulence are all tangled up in a dazzling blur of op and pop. The city is alive with birds (girls) and Beatles, buzzing with Mini cars and telly stars, pulsing with half a dozen separate veins of excitement.” It’s the Swinging London we like to remember – through rose-tinted John Lennon glasses and a haze of incense and marijuana smoke. And you would have to admit, 50 years on, the city hasn’t swung like it since (no, “Cool Britannia” doesn’t come close), and probably never will, now that youth culture has been priced out of the market and creative idling has been all but outlawed by austerity, student loans and terror alerts.

Looking back on the movies of the era, though, a different picture emerges, especially when you start to see London through the eyes of foreign film-makers. By the mid-60s the city had become a magnet not just for dedicated followers of fashion from “the provinces” but also for a steady flow of film-makers, including giants of European cinema such as Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Michelangelo Antonioni and Roman Polanski. They might have been drawn by the “birds” and the Beatles, but, in retrospect, their takes on London’s heyday were often more clear-eyed and level-headed than those of their domestic counterparts. Through the “dazzling blur of op and pop”, they were already sensing undercurrents of paranoia, madness and violence – or did they bring those with them from abroad?

If you had to pick one film that encapsulates Swinging London at its swingingest, you could not do better than Antonioni’s Blow-Up, shot in that golden summer of 1966 and released in the UK in early 1967. It’s all there: the music (the Yardbirds and Jimmy Page on screen, Herbie Hancock on the score), the stars (Vanessa Redgrave, supermodel Veruschka, Jane Birkin, Sarah Miles), the fashions, the parties, the priapic celebrity photographers, the sex (including a then-scandalous flash of pubic hair), and the casual sexism (like Time, David Hemmings’ snapper hero refers to women as “birds”).

But at the same time, Blow-Up is not a particularly swinging film. Like the characters of Antonioni’s earlier Italian hits, Hemmings has it all but does not seem to be enjoying any of it. Instead, in the film’s gripping centrepiece, he rushes back and forth from his darkroom piecing together a murder he is convinced he has photographed. But has he? The film’s conclusion is famously inconclusive: Hemmings watches a group of carefree students silently miming a game of tennis in the park. When they hit their imaginary ball out of the court, he picks it up and throws it back. Was the murder all in his mind? And by extension, was Swinging London anything more than a fleeting collective hallucination? Perhaps it took an outsider such as Antonioni to even suggest such a notion.

It was another foreigner who kick-started the whole scene in the first place. Sexual intercourse began in 1963, according to Philip Larkin, “between the end of the Chatterley ban / and the Beatles’ first LP”. Swinging London cinema began the year after, when Philadelphia-born Richard Lester, who had been working in Britain since the 1950s, channelled the Fab Four’s pop energy into A Hard Day’s Night. With its playful, eclectic visual language and spectacular commercial success (it remains one of the most profitable films ever made), it set the tone for much of what was to follow.

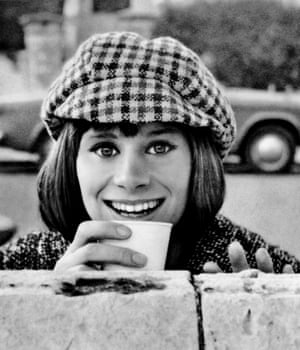

Britain would be inundated with pop films in the coming years, though they were often cheery cash-ins, such as the Dave Clark Five’s Catch Us If You Can, or Lester and the Fab Four’s own inferior follow-up, Help! At best there was Peter Whitehead’s in-with-the-in-crowd doc Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, capturing figureheads such as Mick Jagger, Julie Christie, Michael Caine, David Hockney, Pink Floyd and, of course, Vanessa Redgrave (singing Guantanamera in support of Fidel Castro). Or the perky, poppy satire Smashing Time, in which two of those kids from the provinces (Rita Tushingham and Vanessa’s sister Lynn Redgrave) come to the capital seeking pop stardom, and accidentally find it with the help of an Austin Powers-like producer. Redgrave’s hit song is a perfect parody of London pop, sitars and all. “I can’t sing but I’m young / Can’t do a thing but I’m young,” she sings. It’s pretty catchy.

Meanwhile, Polanski was holing up Catherine Deneuve in a flat and subjecting her to a mental breakdown in 1965’s Repulsion. Deneuve’s Earl’s Court apartment is a stone’s throw from the Kings Road epicentre of Swinging London but it could be on a different planet. No dandies and dolly girls here; only lecherous, leering British men – on the street, in the pub, forcing themselves on her at home. History would reveal Polanski as a flawed spokesman on sexual harassment, but in Repulsion he tapped into the misogyny that seemed to run through 60s Britain, on screen and off.

The only genuinely British-made film to really pick up on these dark currents was Performance, which took 60s hedonism into the realms of mystical mind-altering identity crisis, as Mick Jagger’s reclusive rock star and James Fox’s East End gangster engaged in psychedelic mind games in Notting Hill. Then again, Donald Cammell, the movie’s co-director, was hardly your typical Brit, having lived in Florence, New York and France, though he often seemed a permanent resident of bohemia.

Not that London’s European exiles weren’t having a good time. Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski, Polanski’s friend and former collaborator, came to stay with Polanski several times during those years. They had a great time, he says, frequenting Soho restaurants and discotheques (and the Playboy Club), and rubbing shoulders with various Beatles, Stones and other stars.

“I was looking at London with wide-open eyes,” Skolimowski recalls. “It was such a different world from what I had at home. In Poland, we had the communist system. Everything was gloomy and grey. Practically everybody was wearing the same clothes. In Kings Road, there was music coming from every shop, the crowd had long hair and hippie clothes. Of course, I grew my hair too.”

Skolimowski would make his own contribution to the genre with Deep End, a study of puppy love in a London bathhouse, with Jane Asher (then Paul McCartney’s girlfriend) the object of desire. The film takes a memorable trawl through the sleazy Soho streets and questionable courtship rituals of the late 60s, when a man thought nothing of taking his date to a porn cinema, and a prostitute offers a discount because her leg is in plaster. As with Polanski’s work, the film ultimately turns dark and bleak. “Well,” offers Skolimowski, “Poles are not very optimistic.”

Even Antonioni had a good time in London, it seems. In a later interview, he praised the “happy, irreverent atmosphere of the city,” in 1966. “People seemed less bound by prejudice … They seemed much freer. In some way, I was impressed. Perhaps something changed inside me.” Blow-Up was not pessimistic, he protested, “because at the end the photographer has understood a lot of things, including how to play with an imaginary ball – which is quite an achievement.”

Once they got into the swing of things, in fact, many of these directors lost their edge. Polanski followed up Repulsion with Cul-De-Sac, a lighter-hearted study of domestic madness and unflattering British masculinity, with Françoise Dorléac (Deneuve’s sister) dressing her simpering husband, Donald Pleasence, in a nightie. Then, in 1967, The Fearless Vampire Killers – a pure slapstick horror comedy, starring himself and his future wife Sharon Tate. He only found his dark mojo again when he moved to the US and made Rosemary’s Baby, before the Manson family’s horrific murder of Tate put him in an altogether different place.

Then there was Joseph Losey, another long-term US expat, who had been blacklisted by Hollywood back in the 1950s. In the early 1960s, Losey brilliantly translated Harold Pinter’s savage class satires in The Servant and Accident, with a keen eye for British social nuances. By 1966, though, he was making the camp comic-strip spy thriller Modesty Blaise, with a riot of op-art fashions, Mediterranean locales, and Antonioni’s former muse Monica Vitti as his star. Losey reportedly banned Antonioni from the Modesty Blaise set, since he kept turning up and trying to direct Vitti himself.

Lester won the top prize at Cannes in 1965 for his youthful sex comedy The Knack … and How to Get It, in which Michael Crawford and Ray Brooks vie for the attentions of Rita Tushingham (another “provincial lass” role). But, as the term “sex comedy” suggests, the film has dated rather badly. The corny double-entendres and casual jokes about rape leave a nasty taste, while Lester’s visual trickery – jump cuts, freeze frames, subtitles – only brought home how much he had borrowed from the French new wave.

And by that time, the instigators of the genuine French new wave were in London, themselves. Truffaut came to Britain in 1966 to make his out-of-character sci-fi, Fahrenheit 451. Rather than the swinging city, Truffaut turned his camera on the Identikit suburbs and brutalist housing estates outside the central London bubble. Suburban Britain, as it happened, made the ideal location for a story about a conformist, emotionless, anti-intellectual dystopia. But Truffaut had a torrid time of it. Not speaking the language, he found it difficult to communicate with his English crew, and rarely left his hotel room, while his relationship with his leading man, Oskar Werner, descended into open hostility.

Godard arrived in 1968, all fired up from the Paris riots and seeking to yoke British pop energy to the revolutionary cause (at least that was his excuse). His initial idea was to make a film starring John Lennon as Trotsky, but Lennon was apparently “extremely suspicious” of Godard. But the Rolling Stones let him record them in the studio for five days as they worked out Sympathy For The Devil. These priceless moments Godard intercut with footage of Black Panthers in a Battersea junkyard, readings from Mein Kampf in an adult bookshop and an interview with “Eve Democracy” to form One Plus One – an indigestible collage of radical politics, and one of his worst films. When the movie premiered at the London film festival that November, Godard was horrified to discover his producer, Iain Quarrier, had retitled it Sympathy For The Devil and tacked a complete version of the Stones’ song on to the end. Godard told the audience to come and watch his own cut of the movie, which he would project outside. They didn’t. A shouting match in the National Film Theatre culminated with Godard punching Quarrier onstage. He ended up criticising both the Beatles and the Stones for not being political enough. “The new music could be the beginning of a revolution, but it isn’t …” he told Rolling Stone in 1969. “The Stones are still working for scientific experiment, but not for class struggle or the struggle for production.” Lennon accused Godard of “sour grapes” for them refusing to do his movie.

If Lester switched 60s British cinema on with A Hard Day’s Night, it was another US emigre who switched it off again: Stanley Kubrick, a British resident since 1961. Kubrick had given the hippies their cosmic high with 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 1968. In 1971, he set about giving them the mother of all comedowns with A Clockwork Orange. It is the ultimate anti-Swinging London movie – set in a future where Britain’s socialist dream lies in ruins. As with Fahrenheit 451, the utopian architecture becomes a harbinger of the oppressive future to come. Rather than peace and love, the youth are preaching ultraviolence. The state is adopting brutal techniques to programme free will out of them – using music and movies, of all things, for their aversion therapy. The colourful pop design is still in bloom, but – horror of horrors – now it is the parents who are sporting purple wigs and kinky boots. These parents could well be the Swinging Londoners of Blow-Up and Smashing Time, 20 years down the line, raising rapists and monsters and desperately clinging on to their own lost youth. Bad scene, man. And one made even worse by the moral panic welling in Britain around sex and violence in the movies, which led Kubrick to withdraw the film from British cinemas in 1974.

The buzz was well and truly killed. Free-spirited experimentalism fell out of fashion, and social realism, historical nostalgia and romcoms became the default modes of British cinema. It has become a rarity to see a British film that really captures youth culture (have we had one since Trainspotting?), or pushes the psychedelic boat out. But the sputtering flame of Swinging London has been carried through those the dark ages, and now it burns slightly brighter, thanks to film-makers such as Jonathan Glazer (Under The Skin), Joanna Hogg (Exhibition), Peter Strickland (The Duke Of Burgundy) and Ben Wheatley, whose recent High-Rise felt like a flashback to the good old paranoid, drug-addled, dystopian social breakdowns of the early 70s. Those were the days, eh?

Comments